Hunky Dory, eh? Well, let's start by stating the obvious, shall we? It's a bit bloody good. And everyone seems to love it. How could anyone possessed with a pair of fully functioning ears not? It's a carefully constructed confection, front-loaded with toe-tapping, gorgeous melodies and loving arrangements that feel immediately familiar and 'classic', which would be enough to reward any music loving listener even without probing into the turbulent undercurrents of the lyrical content.

Despite not registering on the charts upon its initial release in December 1971, it's home to three songs which took upon a life of their own within two years of its release - the Beatlesque Oh! You Pretty Things, a huge hit for the newly solo Herman's Hermits frontman Peter Noone earlier that year, the grandiose and wistful Life On Mars? which was to crown a triumphant 1973 for Bowie/Ziggy peaking at Number three in Summer 1973 (note to self: more songs should have punctuation marks in their title) and the album's curtain-raiser, Changes, destined to become the centrepoint of many tours to come and the inevitable soundtrack to numerous documentary profiles on the "chameleon of rock".

These are all undeniable truths, so there's little else to be said on that front, and nothing new to add about how the album as a whole is effectively a prologue for Bowie's imperial phase, lyrically setting the agenda for a decade of artistically and commercially successful reinventions, while musically proving that the boy had songwriting chops, thanks in part to allowing his first great sideman, the self-deprecating and hugely talented Northerner Mick Ronson, to furnish the album's piano-led compositions with soaring string arrangements which swept the listener away and would make Lou Reed's Transformer such a gorgeous album.

But what of your humble scribe's relationship to this album? This is, after all, supposed to be my own personal take on what Bowie's work means to me, enough to be writing about him a quarter century and the rest after discovering his brilliance as a gangly, spotty adolescent. So let's explore my own personal appreciation of this album in some kind of context.

I first got the Bowie bug in the early days in 1987. In March 1986, my family moved to a quiet hamlet on the outskirts of seaside town Milford Haven and shortly after the twentieth century came a-knocking when my parents purchased their first VHS video recorder. For the most part, this was my mother's toy, as she rediscovered her love of Hollywood musicals, taping every RKO and MGM Hollywood musical off the telly in the days when there was rarely a Sunday afternoon which wasn't graced by Sunday afternoon airings of Seven Brides For Seven Brothers or Top Hat. Me, I would have insisted on taping Doctor Who had I not grown apart from my hitherto favourite TV show when the show was 'rested' some months previously - instead, I made sure that my first videotapes were of the show's 1970s peak, as titles from the show's past gradually appeared on home video, at a reduced price, albeit manhandled into 'movie edits', shorn of their cliffhanger endings and reprises.

I do remember the first thing I taped off the telly, as opposed to being gifted to me at Christmas 1986 (Michael Jackson's Thriller, and Revenge of the Cybermen starring Tom Baker). It was a "making of" documentary about the forthcoming fantasy movie, Labyrinth, written by Monty Python's Terry Jones, directed by Muppet supremo Jim Henson and produced by George Lucas of Star Wars fame. It also starred some bloke called David Bowie, who curiously had not really come across my radar, despite having been an avid fan of pop music as a child of the '80s - somehow Mr. Bowie had passed me by despite the huge success of Let's Dance in 1983, a great year for pop in which I was transfixed by Top of The Pops' weekly broadcasts. I was vaguely aware of Dancing In The Street and Absolute Beginners, which had been his two biggest recent hits, and was soon to discover that I did know of Space Oddity and Starman, due to owning a Pickwick childrens' EP some years previous titled Journey Into Space, as covered by sound-alike anonymous musicians.

The Making of Labyrinth was aired sometime around Christmas 1986, and it was stuck on the end of a JVC E180 after Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. I suspect the tape is landfill now, or in the darker recesses of my parents' attic.

This documentary of Labyrinth really captured my imagination. The creativity of the Jim Henson Creature Workshop was showcased in a way that fascinated me, and I loved fantasy films, which enjoyed something of a heyday back in the '80s when practical effects hadn't yet been overtaken by digital wizardry - I'd adored The Dark Crystal, Krull, Legend, Willow and The Princess Bride after all. To be honest, what most captivated me about The Making of Labyrinth were the contributions of Terry Jones, its voluble, excitable and very animated Welsh scriptwriter. A few months after this documentary was aired, I was to discover Monty Python's Flying Circus, when the BBC re-ran its second series, and I was entranced by its upside-down world when the self-same Terry Jones, in full drag as a cuddly suburban housewife, hopped over a garden wall shortly before consenting to being poisoned by men from the Gas Board purely to fulfil some terms and conditions of his/her new cooker. Little did I know that four years later, I would start a Monty Python fan club, and in 2013, I would be sat in the great man's house, discussing Ripping Yarns, Christopher Columbus and Federico Fellini over bottles of wine. But that's another story.

A short while after being captivated by this teaser of Jim Henson's latest slice of fantasy, a cinema trip was arranged for my eleventh birthday in January 1987, where me and some of my closest school friends saw Labyrinth on the big screen. Suddenly, I was a Bowie fan, Tina Turner fright wig, inappropriately revealing jodhpurs, funny-coloured eyes and all. And that voice. I don't think I'd heard a singing voice like it - keening and urgent during Underground, playful and incongruously soulful in Magic Dance and utterly bewitching and seductive during the Escher-inspired highlight that was Within You. Oh, and he had funny coloured eyes, did I mention that?

Bowie became an instant crush and obsession. Despite having no income to speak of, I was determined to discover more about this otherworldly man with the strange London accent and peculiar presence. Come Easter 1987, a record token was exchanged in the Burton upon Trent branch of Our Price for a cassette of the Dame's latest Never Let Me Down. You may scoff, but up to that point my understanding of pop was that it was all about skiving from school, boyfriend/girlfriend troubles and the cult of Americana. In its stead, this very '80s album was singing about things I had no register with - homeless couples, vampiric figures trapped in a narcissistic hall of mirrors, neediness and insecurity, nuclear fallout, mutant spiders from outer space and other forms of weapons grade weirdness. Plus, the title track had the weirdest, jerkiest rhythm I had ever heard, and a bizarre falsetto that was strangely fascinating.

So I absorbed what I could, which was no mean feat when I could not afford those fancy, new-fangled compact discs (which, in Bowie's case, were soon pulled from the shelves as he began extricating his back catalogue from RCA) and did not own a record player with which I could play those cheap 1980s reissues of his 1970s albums on RCA International, instead all I could do was gaze with curiosity at their freakish covers of this Bowie chap in various unknowable guises.

I amassed a handful of chunky cassettes - Low, Tonight, Changesonebowie, Ziggy Stardust, Diamond Dogs and Aladdin Sane. Some I bought myself, some I purchased during a shameful period of pick-pocketing (said Bowie tapes were amnestied by my parents when they got wind of my criminal ways, until I proved I could behave impeccably, and it was the longest summer ever), and I had to fill in the gaps myself when I would catch the occasional Bowie random track on Annie Nightingale's request show or BBC2's The Rock & Roll Years.

It all changed when I made another friend at comprehensive school. There was a girl three years above me, called Karen, and she seemed impossibly exotic to me at my young, impressionable age. She had blonde streaks in her fringe much like Thomas Jerome Newton, and her army surplus schoolbag was festooned with Bowie patches. Until I went to University, I was socially inept and chronically shy, so I stalked her in a benign fashion until I could engineer a "hello, I like David Bowie too" moment.

Worth bearing in mind, here, that there was nothing less fashionable in 1987-1988 than being a David Bowie fan, speaking from my own experience. The fact I was listening to Low in 1988 would have made me a hipster by modern standards, but instead it just made me look weird to my classmates, then in thrall to Yazz, Jive Bunny, Belinda Carlisle, Big Fun and the like.

Anyway, a connection was made, and me and Karen began a very complex arrangement of meeting on the steps outside the Sixth Form Common Room during lunch breaks, swapping Bowie books, clippings and cassettes. Turned out that only RCA albums available on cassette in Woolworths that I hadn't snapped up were the ones she'd bought.

Karen also owned vinyl. I could actually play David Bowie singles and albums on my parents' antiquated sound system and record them on my blank tapes, thus engorging my tiny collection. In an era of freely downloadable stuff, it is hard to explain to younger generations what a big deal this was.

Hunky Dory was one of those albums. It was a 1982 reissue under the RCA International imprint, having read so much about this album in my bibles at the time, Dave Thompson's Moonage Daydream and the Roy Carr/Charles Shaar Murray An Illustrated Record - a beauty of a book, which I spent whole hours pouring over in WH Smiths until I'd manhandled it so much, it ended up in their bargain bin and I snaffled it up after begging my dad to lend me the requisite two quid. His response? "I thought you'd grown out of that Bowie chap?". This was 1988. He tried to cure me by making me listening to Nat King Cole once. Hello, Dad!

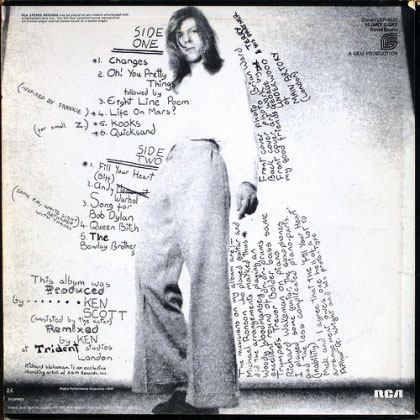

I wasn't quite prepared for Hunky Dory, and yet simultaneously it lived up to all my expectations. We have to start with the album cover. I've always been fascinated by androgyny, and coupled with having a Golden age of Hollywood fangirl for a dear Mother, the sleeve of Hunky Dory was very suggestive of Greta Garbo, Lauren Bacall and Veronica Lake. Its saturated, hand-coloured tones and gauzy screen-print effect called to mind so many Hollywood front of stall stills I'd seen in my Mum's collections. And yet flip the LP cover, and you see David, still with long hair, but very out of focus, and wearing the most god-awful pair of massive flares (which I have since learned were made by Paul Smith, the now famous fashion designer) and looking decidedly dowdy. The back cover was also festooned with Bowie's spidery and autistic handwriting, giving it a personal touch.

I remember the first time I let the needle drop on this flimsy, 1980s vinyl pressing. Of course, I knew Changes well, as the compilation it gave its name to - Changesonebowie - had been a permanent fixture in my listening habits (along with Beastie Boys' Licensed to Ill, A-Ha's Scoundrel Days and Pet Shop Boys' Actually) in late 1987, purchased in Boots The Chemist, but the rest of it... It was strangely comforting.

I had no idea of the context, as Karen didn't loan me this album's immediate predecessor, The Man Who Sold The World, until a few months later, but I do recall popping the thin black vinyl onto the spindle, dropping that delicate needle, gazing at the bile-green centre label, closing the mahogany doors of the hi-fi cupboard, snuggling into my parents' most comfortable and upholstered easy chair, the kind that envelops you like a massive hug, and donning a massive pair of headphones, so as not to disturb my youngest brother, then in the thrall of the VHS of Tubby The Tuba for the millionth time.

Hunky Dory is an album that is simultaneously comforting and disturbing. You're immediately seduced by Bowie's pop nous and keen way with hooks and melodies, and Mick Ronson's sumptuous string arrangements, and the glissandos of Rick Wakeman's piano, that it's so easy to see why it sits alongside the likes of Carole King's Tapestry as an album much loved by young couples who got together in the early 1970s and became homebodies - much like my beloved parents, in fact, and indeed Angie and David with young Zowie - but nothing prepares you for the chthonic enigma that is The Bewlay Brothers, the clash of opposing belief systems and philosophies epitomised in Quicksand's spiritual battle (continuing the dialogue of Holy Holy and The Width Of A Circle) and the admixture of homely domesticity and eerie prescience of supernatural evolution onto another plane that beds down both Oh! You Pretty Things and Kooks. In the nicest possible way, it's a turd in a chocolate box. There's some heavy stuff in Hunky Dory, existentially speaking, and yet couched into a musical form that by Bowie's own admission, is based upon Paul McCartney's Martha My Dear or Maxwell's Silver Hammer.

I shit you not, after hearing The Bewlay Brothers in the comforting arms of my parents' "hi fi chair", the walk back upstairs to bedtime was terrifying.

The album occupies spaces elsewhere that are less threatening. Bowie's rendition of Biff Rose's hippie anthem Fill Your Heart is genuinely joyous - at least until you clock that the vocal's manic style is not far off that of the deranged, Fugazi'd Vietnam vet gone native in Running Gun Blues.

What I love about Hunky Dory is that it is simultaneously intimate and domestic, and also otherworldly and uncanny. On the surface, it's pretty and melodic and homely, but there's so many undercurrents of the phantoms that haunted Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold The World - fears of the unknown, the uncanny, what it would mean for a paradigm shift in how we adjust to entering another phase of spiritual evolution, which is as scary as it is exciting, and that we are all stumbling around, looking for answers like "a prophet or a stone age man... a mortal with potential of a superman...". The fever and dark in the mindwarp pavilion, the crack in the sky, turning to face the strange.

And, of course, we have to mention the trilogy of hero worship songs - Andy Warhol (as in holes), Song For Bob Dylan and Queen Bitch. In context, these are nothing less than mission statements, Bowie has absorbed all the lessons he can learn from his titular heroes, and is gonna show us, "Oh God, I can do better than that."

By the time Hunky Dory was in the shops, Ziggy Stardust was virtually in the can. It really would be the freakiest show.

And you know what? Whenever I listen to Hunky Dory, I am still the boy in the headphones.

Blogalongabowie

9th March 2014.